NOVEMBER- NATIONAL ADOPTION MONTH

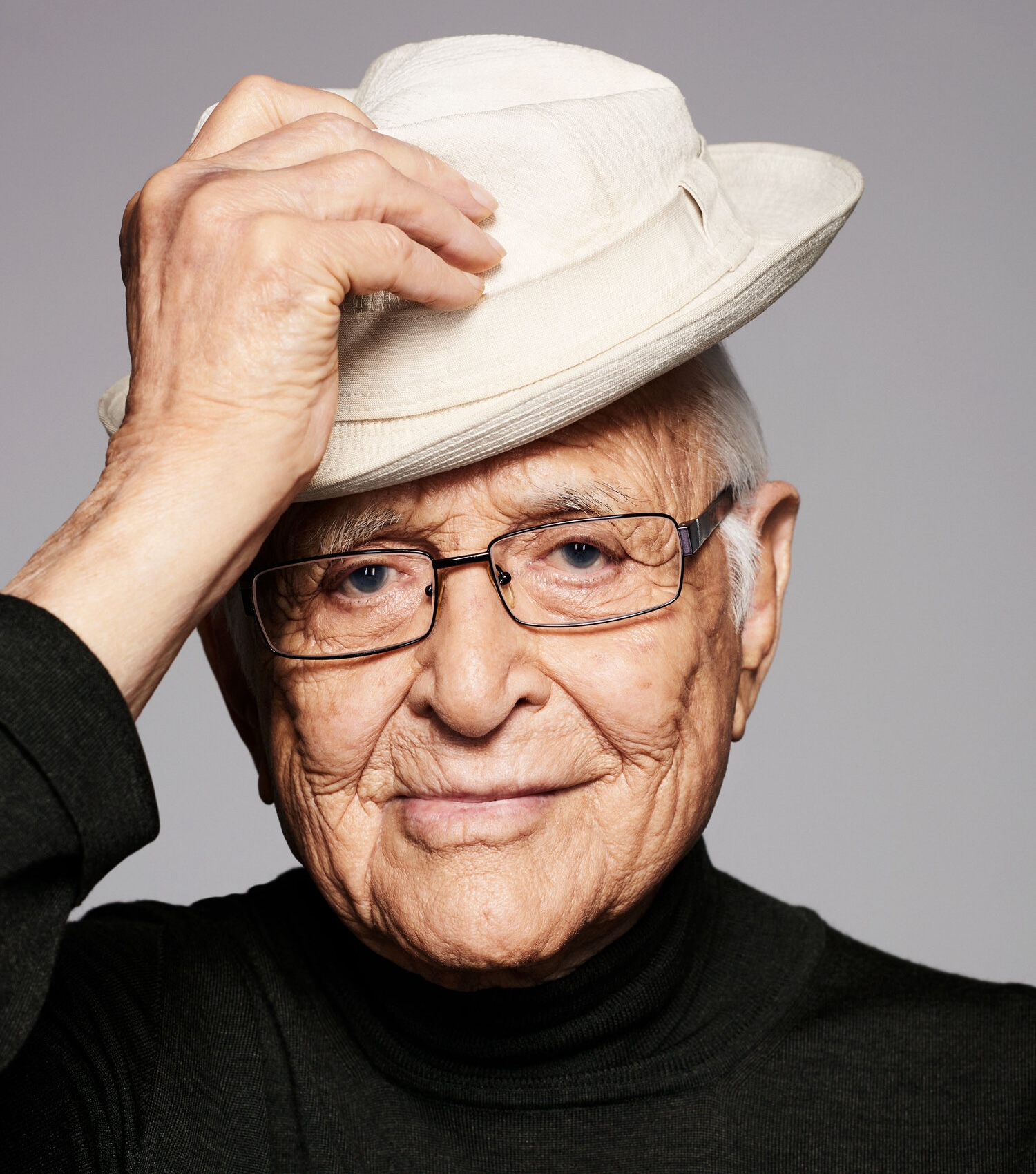

Please click here to view the photo story of Brandi’s adoption!

“I never said I wanted to adopt, ” I explained once again, to the Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services’ social worker.

As a single mother, having already raised five children who, at the time of this challenge from the Department, ranged in age from 25- 38 years, I was not about to relive the tremendous responsibility that accompanies raising children in a low-income home with the high expectation of them becoming productive and successful adult members of society.

“Permanency is our goal,” was the concept the social worker continually wrapped into her home visit conversations.

Brandi Armstrong had been placed with me on June 6, 1991, when she was 2 days old. She was brought directly from the hospital nursery. Brandi was placed in protective custody because her mother tested drug positive.

Back then, Brandi and thousands like her were called “drug babies”. Before she was placed in my foster home, I had cared for 12 other newborn drug babies. In each case, either family members were awarded custody within three months of placement, or the mother followed court orders and did her drug recovery plan and reclaimed her child.

Not so in Brandi’s case. No family member surfaced. I was her mom and my children and other relatives became her family.

However, at the age of three, the Department demanded I adopt her or said they would find permanent placement through adoption.

Every child in the foster care system is assigned an attorney. Fortunately for Brandi, her attorney was more concerned with her best interests than he was with the number of adoptions the Department was able to initiate and finalize.

“Guardianship without Department oversight,” he said to me.

This would mean that Brandi would remain under my care–permanently. Guardianship meant she would be removed from the Department’s roster of children eligible for adoption.

There was a prospective single parent for Brandi who was seemingly, a good person who picked up Brandi from my home on many occasions for full-day visits. This prospective mom had taken parenting classes and had passed other department requirements to become an adoptive parent.

Only one thing stood in the way of this becoming the Permancy the Department claimed to believe in.

While serving as Chair of the Los Angeles County Adoption Commission, I came upon two of the more troubling aspects of the placement process. One was the lack of disclosure–that is, providing a comprehensive report detailing the mental and physical health of a child. The other troublesome aspect was the Department’s policy allowing adoptive families to end the placement by returning the child back into the system.

Both of these policy positions, I knew, would work against Brandi. No matter how committed this prospective mom was, she lacked information regarding the skills needed to parent a child like Brandi.

Research shows that drug-addicted infants, among their many problems, are extremely irritable. They frustrate easily, have a short temper, and are startled at the simplest sound. The babies often struggle with an irregular sleep pattern and can be very hyperactive despite the lack of rest they manage to get.

Brandi went through these early withdrawal symptoms and many more, but her challenges didn’t go away as she grew older.

By the time Brandi was three years old and in the County’s adoption loop, she was diagnosed with ADHD with Asperger’s – a form of Autism.

Her day-to-day behavior and inability to function like other children her age were a tremendous challenge as her preschool teacher would testify in the court proceedings that awarded me Guardianship over the Department’s request for adoption.

Unheard of in the Foster Care System, at the age of 3 Brandi had remained in the same placement since birth. A circumstance that made, I’m sure, an impact on the decision of the court along with witness testimony that focused on Brandi’s inability to accept even minor changes in her life.

A drug-addicted baby may also experience repercussions later in life. These include motor skill delays and the inability to interact and socialize with peers properly. Many babies born addicted to drugs go on to struggle with behavior issues once they are school-aged. The ability to sit still, focus, and maintain personal boundaries are sometimes great feats for them, and their problems are often resolved only with therapy, a modified educational plan, and/or prescription medication.

Brandi’s symptoms have persisted into adulthood. She is now 24 years old, but with therapy, medication, modified education plans, and a huge community and family support system she functions well.

On a warm July day of 2015, I returned to Los Angeles County Edelman Children’s Court where twenty years earlier I had been awarded guardianship.

Now, I was back with Brandi and her same attorney to finalize an adoption he had filed papers for just a few months earlier.

Why now in 2015? That’s another story!